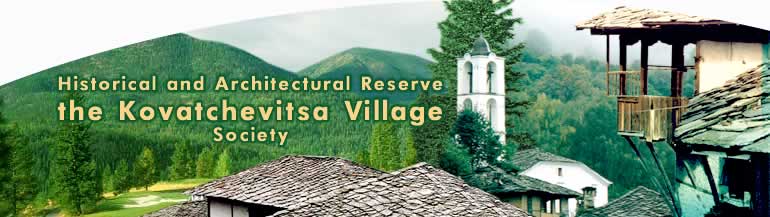

| Kovachevitsa Back to History | пїЅпїЅпїЅпїЅпїЅ пїЅпїЅ пїЅпїЅпїЅпїЅпїЅпїЅпїЅпїЅпїЅ пїЅпїЅпїЅпїЅ |

|

Kovachevitsa Back to Historyby Mihail Enev Ph.D.

Click here to download the original brochure in .pdf file - 2.31 MB |

A Tale of Stone and Wood“Simplicity underlies finest taste” |

|

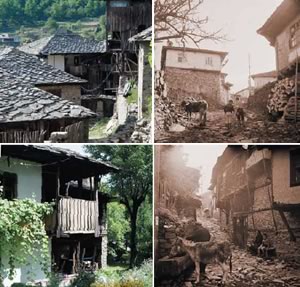

Viewed from a historical perspective the architecture aspects of the village prior to the arrival of the emigrants from the Debar, Kichevo and Tetovo Regions in 1791 were almost wiped out. The new professional interventions is so strong such as to acquire gradually almost all architecture spaces in order to leave our modernity a masterpiece of a unique accord of styles! |

|

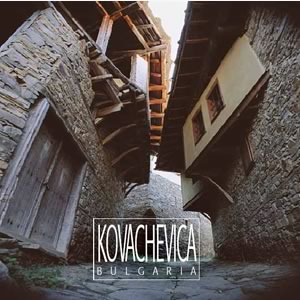

Some facts of the past that provoke curiosity and amazement also today in view of the unique construction of the public utilities in the village evidence the building talent and foresight: for instance the pipeline, which was based on a modern technology at that time dug into the rocky alley terrain at depth of 2.5 m! The unique alley pavements with a drainage denivelation of the rain water with included cross thresholds of stone plates that prevented from happening sliding on the extremely steep terrain in the winter could also be deemed as construction models. |

The eaves

of the houses clustered in between at many points that cast a deep shadow on the

cobblestone pavements and brought a nice sense of coziness in hot summer times,

were also fine shelters against snow drifts in times of harsher winters. These

picturesquely mazy narrow village alley without sidewalks were one of the most

attractive relaxation places especially next to one of the 12 fountains that filled

with life and poetry the ancient architecture. The house walls solidly standing

right on the alley pavement does not bother the eye, as their forms were softened,

the sharp edges were rounded by the caring hand of the builder such as to ensure

comfortable and save movement of people, carts and stock. The eaves

of the houses clustered in between at many points that cast a deep shadow on the

cobblestone pavements and brought a nice sense of coziness in hot summer times,

were also fine shelters against snow drifts in times of harsher winters. These

picturesquely mazy narrow village alley without sidewalks were one of the most

attractive relaxation places especially next to one of the 12 fountains that filled

with life and poetry the ancient architecture. The house walls solidly standing

right on the alley pavement does not bother the eye, as their forms were softened,

the sharp edges were rounded by the caring hand of the builder such as to ensure

comfortable and save movement of people, carts and stock. |

|

Along the stretch of the houses two- or three-floored one of top of the other the ceilings were made of timber. The visible main structures of the roofs made of 10-15 m planks that impressed even the most critical eye with its master processing, added the new feeling of warmth provoked by the noble color of timber. |

|

It would not be hard to imagine the understanding among people and the participation of the entire working population in the process of building each new house. The latter was the main reason for the synchrony reached between the mixture of complicated “Г”-shaped or “П”-shaped rows and groups of houses that formed the compact carpet-like building of the village. Once again the main reason for the rich and extremely functional building was the lack of terrain. Scarce and steep, the latter imposed the differentiation of the residential environment in Kovachevitsa into three zones: residential center zone, a layer of agricultural premises (for weeding, granaries, etc.), and outside the latter also a zone of agricultural areas. That structure of the village was preserved for a long time since it was the most natural and successful solution for adequate existence of the population. |

|

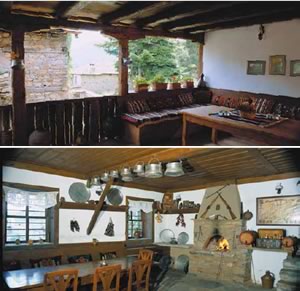

In the 19th century the structure of the family houses underwent a significant change after the separation of separate families in individual rooms with fireplaces. The interior was enriched by building specialized premises that noted the advanced everyday manners of the Kovachevitsa community. The most popular interior structures were as follows: “ceiling — ponton” (salon – hall way) with an adjunct step-ladder thereto fully made of timber via which a link could be made with all other premises; vodnik (water storage for daily necessities); kyoshk – resting room; independent rooms with fireplaces and ovens sometimes linked with the ceiling. The ceiling remains the most interesting interior element even from a modern point of view. Always directed to the best view, the latter defined also the visual and space solution of the main fa?ade of the house, as it integrated very strikingly in the assembly type of the fraternal houses. Various architecture schemes of the situation of the ceiling: longitudinal, cross, symmetrical, and central-transverse determines the differences in the facades of the Kovachevitsa house. The talented craftsmen did not stop importing variety into each new house as they exported further one-sided, two-sided or threesided balconies with wide eaves. They also enriched the architecture and construction elements with peculiar details on the parapets, and the wooden wall-curtains of the eaves. The moderate use of the socalled joiner’s fretwork on ceilings, doors, garrets, and column ends, visible from the outside was in full harmony with the austere style of the interior. |

|

The significant construction achievements of the Kovachevitsa masons indisputably originated from the expertise passed on as a family tradition, but also in the customary legal norms observed by everyone that regulated the relations in the league in view of hierarchy, arrangements, labor distribution, and profit allocation. The gradual introduction of hired labor under the waged-based form in the mason groups at the end of the 19th century was a prerequisite for a new statute and hierarchy in the construction guild. It is known to me that in Kovachevitsa a Management Board used to be selected of the most prominent masters that presented the image of the mason profession in society. Shops for specialized instruments were opened and competition rendered the craftsmen create a secret language of theirs referred to as “meshtrovsky” or “meshtrogansky” of the type of social dialects close to the Bratzigovo one and fully incomprehensible to the uneducated ones, as more than 300 meshtrogansky words and phrases have been preserved. |

Only memories

passed on by word from one generation to the next have remained from the tremendous

construction times of Kovachevitsa. One could hear a word or two even today about

the large Vris bazaar in the center and the twenty shops located there from the

Shubalekov fountain to the Landjov one, named after local families, about the

smithy, the packsaddle’s shop, the forge, the shoemaker’s shop, the tailor’s shop,

the confectionary, and the grocery. They still exist in the memories of the few

local residents. Some of them used to run as kids on the Vris bazaar and used

to enjoy the unique big market on which villagers and merchants of the neighboring

villages used to come to offer their various goods. In the 50s of the last century

the new road built to the Beslet Forestry put an end to the diversity and tumult

because it passed right in the middle of the bazaar destroying all commercial

buildings. The unique inn (the Bakalov House) that had used to be in the very

center of the bazaar was also demolished. Fortunately, not all public sites were

damaged. The public-spirited community of Kovachevitsa saved the most precious

monument of effort of the entire community, it used to be a symbol of hope of

better life, confidence, and protection of suffering. Therefore, they dedicated

it to St. Nikola, a guardian of the strangers, workers, and refuges as the entire

community originated there of. Only memories

passed on by word from one generation to the next have remained from the tremendous

construction times of Kovachevitsa. One could hear a word or two even today about

the large Vris bazaar in the center and the twenty shops located there from the

Shubalekov fountain to the Landjov one, named after local families, about the

smithy, the packsaddle’s shop, the forge, the shoemaker’s shop, the tailor’s shop,

the confectionary, and the grocery. They still exist in the memories of the few

local residents. Some of them used to run as kids on the Vris bazaar and used

to enjoy the unique big market on which villagers and merchants of the neighboring

villages used to come to offer their various goods. In the 50s of the last century

the new road built to the Beslet Forestry put an end to the diversity and tumult

because it passed right in the middle of the bazaar destroying all commercial

buildings. The unique inn (the Bakalov House) that had used to be in the very

center of the bazaar was also demolished. Fortunately, not all public sites were

damaged. The public-spirited community of Kovachevitsa saved the most precious

monument of effort of the entire community, it used to be a symbol of hope of

better life, confidence, and protection of suffering. Therefore, they dedicated

it to St. Nikola, a guardian of the strangers, workers, and refuges as the entire

community originated there of. |

|

A vast three-row iconostasis fully made of wood with an extremely beautiful royal entrance welcomes the worshippers with its awesome magnificence. The sacral mysticism of the church is reinforced more than 70 icons arranged in three horizontal rows. |

The twenty

royal icons of the middle of the 19th century were created by an anonymous icon-painter

that bore the marks of the late icon-painters of the Tryavna Painting School.

The colors, the composition solutions and the painting technique were undoubted

executed by a fine brush master the created unique images of the late Renaissance

icon-painting. The apostolic and celebration row of icons in the iconostasis was

made by other anonymous icon-painters. On the Northern and Southern walls close

to the iconostasis were placed arcs of two extremely precious icons: St. George

and a Horse and St. Dimitar and a Horse created by the hand of Georgi Stregyov

in 1874 of the Balkan Artistic School. The twenty

royal icons of the middle of the 19th century were created by an anonymous icon-painter

that bore the marks of the late icon-painters of the Tryavna Painting School.

The colors, the composition solutions and the painting technique were undoubted

executed by a fine brush master the created unique images of the late Renaissance

icon-painting. The apostolic and celebration row of icons in the iconostasis was

made by other anonymous icon-painters. On the Northern and Southern walls close

to the iconostasis were placed arcs of two extremely precious icons: St. George

and a Horse and St. Dimitar and a Horse created by the hand of Georgi Stregyov

in 1874 of the Balkan Artistic School. |

The church

complex was fully completed as late as 1900 when the Kovachevitsa people gained

courage and money to raise without an official permit a 12-m tall bell tower in

the church yard. In the latter four-floor tower they placed 2 large bells cast

by Goren Brod craftsmen as a donation by the Alexov brothers. On the eastern side

of the tower also the first clock was installed that measured time by the beat

of the clock hammer on the bells. Thus the ring sound with its melodic sound accompanied

Kovachevitsa people on every hour in their hard days and spread a rich tune of

the two bells on holydays. Unfortunately the clock did not survive to our times.

The buildings of the St. Nikola Church, the Cell School and the Elementary School

“Yordje Dimitrov” linked in a unique architecture complex as well as many of the

old village houses have a status of Architecture Culture Monuments in compliance

with the provisions of the Law of Culture Monuments and Museums. The church

complex was fully completed as late as 1900 when the Kovachevitsa people gained

courage and money to raise without an official permit a 12-m tall bell tower in

the church yard. In the latter four-floor tower they placed 2 large bells cast

by Goren Brod craftsmen as a donation by the Alexov brothers. On the eastern side

of the tower also the first clock was installed that measured time by the beat

of the clock hammer on the bells. Thus the ring sound with its melodic sound accompanied

Kovachevitsa people on every hour in their hard days and spread a rich tune of

the two bells on holydays. Unfortunately the clock did not survive to our times.

The buildings of the St. Nikola Church, the Cell School and the Elementary School

“Yordje Dimitrov” linked in a unique architecture complex as well as many of the

old village houses have a status of Architecture Culture Monuments in compliance

with the provisions of the Law of Culture Monuments and Museums. |

© Society пїЅHistorical and Architectural Reserve Village KovachevitzaпїЅ

The worldly wisdom of the great French

sculptor Auguste Rodin most accurately fits the architectural expression of

the self-made construction genius of the modest Kovachevitsa masons. Simplicity

elevated to perfection in the architecture assembly as a whole and its magnificent

details is the most noteworthy merit of the unique style of the Kovachevitsa

Construction Architecture School. It would be difficult to find elsewhere such

an impeccable architecture synthesis between natural environment and building

miracle created by human hand. We would only be grateful today for the existence

of this tale of stone and wood in which the complete splendor of local spirit,

diligence and talent of the Renaissance Kovachevitsa are entwined.

The worldly wisdom of the great French

sculptor Auguste Rodin most accurately fits the architectural expression of

the self-made construction genius of the modest Kovachevitsa masons. Simplicity

elevated to perfection in the architecture assembly as a whole and its magnificent

details is the most noteworthy merit of the unique style of the Kovachevitsa

Construction Architecture School. It would be difficult to find elsewhere such

an impeccable architecture synthesis between natural environment and building

miracle created by human hand. We would only be grateful today for the existence

of this tale of stone and wood in which the complete splendor of local spirit,

diligence and talent of the Renaissance Kovachevitsa are entwined. The Debar

builders that in several generations turned into Kovachevitsa ones appreciated

natural beauty and therefore not only did they not impair it, but further skillfully

integrated their creations into the limited unity with nature. Today we cannot

miss expressing our admiration for the approach and mode of situating and constructing

the houses, the building of ancillary economic premises, commercial, public

ones, etc. and the link in between, the unique stone arteries – the alleys compliant

with natural resources: a scarce, steep, and rocky terrain.

The Debar

builders that in several generations turned into Kovachevitsa ones appreciated

natural beauty and therefore not only did they not impair it, but further skillfully

integrated their creations into the limited unity with nature. Today we cannot

miss expressing our admiration for the approach and mode of situating and constructing

the houses, the building of ancillary economic premises, commercial, public

ones, etc. and the link in between, the unique stone arteries – the alleys compliant

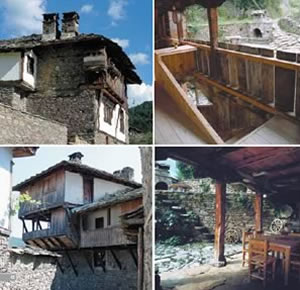

with natural resources: a scarce, steep, and rocky terrain.  The notion

of saving the construction space led to extremely rational architecture solutions

that impress with its logic and completeness. Each of the Kovachevitsa houses

in itself was a unique architecture solution of the general task: to achieve

maximum residential space with minimum means. Therefore, the common feature

of the houses is the development of the built-up area on the vertical axis as

the space in the basis is the tightest and the most limited and the expansion

unveils in elevation. Timber used by the craftsmen in the lower register of

the houses at scattered places only in the form of koshak (reinforcement) in

the solid two-folding entrance doors and some small service windows, created

a general impression of the houses of being stone Middle Age fortresses. They

resembled defense towers standing on guard in the midst of the village raised

right from the rocky landscape and reaching high with 3-4 floor size structures.

Naturally, the latter notion was brief until the eyes reached the upper floors

where the gifted builder demonstrated extravagance using timber.

The notion

of saving the construction space led to extremely rational architecture solutions

that impress with its logic and completeness. Each of the Kovachevitsa houses

in itself was a unique architecture solution of the general task: to achieve

maximum residential space with minimum means. Therefore, the common feature

of the houses is the development of the built-up area on the vertical axis as

the space in the basis is the tightest and the most limited and the expansion

unveils in elevation. Timber used by the craftsmen in the lower register of

the houses at scattered places only in the form of koshak (reinforcement) in

the solid two-folding entrance doors and some small service windows, created

a general impression of the houses of being stone Middle Age fortresses. They

resembled defense towers standing on guard in the midst of the village raised

right from the rocky landscape and reaching high with 3-4 floor size structures.

Naturally, the latter notion was brief until the eyes reached the upper floors

where the gifted builder demonstrated extravagance using timber. The abundance

of timber of the finest quality in the vicinity gave several centuries the liberty

of the craftsmen to create the unique interior of the Kovachevitsa house. The

timber-made couches, the embedded furniture, book shelves, closets, columns

and anything else required by the home customs and coziness passed through the

hands and the hearts of the original craftsmen from Tetovo, Kostur and Debar

characterized by proverbial expression simplicity and beauty. Extreme ornateness

and eclectics typical for Renaissance houses in other regions of the country

were not present here. No object existed unless having a functional purpose.

Simply what was useful became beautiful as well. Harsh life and living of people

for centuries were reflected in the modest, simple interior architecture even

in the residential premises number, type and functionality. The famous Kovachevitsa

houses referred to as “fraternal” reflected the philosophy of input labor and

equal relations in the family and lineal patriarchal life. In the assembly of

two to three houses none of them dominated. They situated on the terrain such

as to avoid hindering one another, competing, robbing one another of the space

and light. Such an interaction of volumes in the architecture composition reached

in the fraternal complexes did not have an analogue in the records of the Bulgarian

Renaissance architecture thought.

The abundance

of timber of the finest quality in the vicinity gave several centuries the liberty

of the craftsmen to create the unique interior of the Kovachevitsa house. The

timber-made couches, the embedded furniture, book shelves, closets, columns

and anything else required by the home customs and coziness passed through the

hands and the hearts of the original craftsmen from Tetovo, Kostur and Debar

characterized by proverbial expression simplicity and beauty. Extreme ornateness

and eclectics typical for Renaissance houses in other regions of the country

were not present here. No object existed unless having a functional purpose.

Simply what was useful became beautiful as well. Harsh life and living of people

for centuries were reflected in the modest, simple interior architecture even

in the residential premises number, type and functionality. The famous Kovachevitsa

houses referred to as “fraternal” reflected the philosophy of input labor and

equal relations in the family and lineal patriarchal life. In the assembly of

two to three houses none of them dominated. They situated on the terrain such

as to avoid hindering one another, competing, robbing one another of the space

and light. Such an interaction of volumes in the architecture composition reached

in the fraternal complexes did not have an analogue in the records of the Bulgarian

Renaissance architecture thought.  The Kovachevitsa

houses similar to the Rodopi houses in general were solid stone-made buildings

with peculiar masterfully executed masonry. The building technology was quite

simple: mozaically arranged non-hewed stones cemented with soft soil. The solid

masonry was extremely firm and its duration has been verified by time, and the

beauty of the overflowing ochre to a cold gray stone mosaic was indisputable.

The thin patina-covered-over-time reinforcement (koshatzi) separating the stone

masonry into horizontal layers introduced a human dimension and a decoration

response of the austere stone areas. The Kovachevitsa masons left also their

unique construction mark on the timber frame of the top structures, the windows,

the doors, the timber oriel paneling and naturally on the simple and laconic

architecture detail of the interior. Entering into the traditional Kovachevitsa

house, a prototype of the Rodopi one, one should first pass through the “dry”

yard next to which the podnik (cattle-shed) was situated in the lowest register

of the building. If an economic floor were present, usually developed at a semi-level,

one could reach it using a large timber step-ladder. The following one or tow

floors were designed to accommodate the crowded families. In the initial type

of construction that lasted until the 17th century the large families inhabited

a big room with a fireplace that functioned both as a bedroom and a living room.

The Kovachevitsa

houses similar to the Rodopi houses in general were solid stone-made buildings

with peculiar masterfully executed masonry. The building technology was quite

simple: mozaically arranged non-hewed stones cemented with soft soil. The solid

masonry was extremely firm and its duration has been verified by time, and the

beauty of the overflowing ochre to a cold gray stone mosaic was indisputable.

The thin patina-covered-over-time reinforcement (koshatzi) separating the stone

masonry into horizontal layers introduced a human dimension and a decoration

response of the austere stone areas. The Kovachevitsa masons left also their

unique construction mark on the timber frame of the top structures, the windows,

the doors, the timber oriel paneling and naturally on the simple and laconic

architecture detail of the interior. Entering into the traditional Kovachevitsa

house, a prototype of the Rodopi one, one should first pass through the “dry”

yard next to which the podnik (cattle-shed) was situated in the lowest register

of the building. If an economic floor were present, usually developed at a semi-level,

one could reach it using a large timber step-ladder. The following one or tow

floors were designed to accommodate the crowded families. In the initial type

of construction that lasted until the 17th century the large families inhabited

a big room with a fireplace that functioned both as a bedroom and a living room.

The flexible

dynamics of the oriels exported above the stone facades of the Daskalov House,

the Sarafov House, the Bangov House, the Urdev House, etc. exemplified the early

Renaissance Rodopi architecture. The assemblies of the Dishlyanov House, the

Shumarev House, the Pilarev House, the Gyuzelev House, the Kyupov House as well

as the large group of the Shimerov Houses had a unique impact and architecture

and artistic virtues. All of the latter as well as the other Kovachevitsa houses

owed their stylistic completeness to the stone top made of a beautiful mosaic

of the famous tiles, riolyte plates, each one with a different shape obtained

by manual processing and having natural patina. The Kovachevitsa would not have

been harmoniously complete architecturally without that authentic architecture

feature.

The flexible

dynamics of the oriels exported above the stone facades of the Daskalov House,

the Sarafov House, the Bangov House, the Urdev House, etc. exemplified the early

Renaissance Rodopi architecture. The assemblies of the Dishlyanov House, the

Shumarev House, the Pilarev House, the Gyuzelev House, the Kyupov House as well

as the large group of the Shimerov Houses had a unique impact and architecture

and artistic virtues. All of the latter as well as the other Kovachevitsa houses

owed their stylistic completeness to the stone top made of a beautiful mosaic

of the famous tiles, riolyte plates, each one with a different shape obtained

by manual processing and having natural patina. The Kovachevitsa would not have

been harmoniously complete architecturally without that authentic architecture

feature.  The story

of the permit obtained hard from the Turkish Authorities to build the church

turned into a local legend tells for a famous Kovachevitsa merchant that managed

to receive recognition even in the Sultan’s Court in Tzarigrad as being a skillful

barber. His fellowvillagers asked him for assistance since it had been impossible

for them to receive a construction permit from the Sultan Administration (the

High Gate). The latter was done by Sultan himself who issued and signed a firman

for the construction of the Kovachevitsa church as a sign of benevolence and

recognition of the Kovachevitsa barber’s talent. The only condition was that

it should not be raised tall in order not to been seen from a large distance.

Therefore, the builders dug the church into the ground and yet preserved its

large size in the interior. The entire community worked to build this God’s

temple and maybe that is the reason why the craftsmen forgot to engrave their

names in a commemorative tablet on the wall or probably the sponsors were that

numerous and it was difficult to fit onto one wall. The church was completed

and sanctified in 1848. The St. Nikola basilica with a nave a two aisles, one

of the five largest basilicas in Bulgaria, was built following the traditional

Kovachevitsa technique and materials, solid stone walls and top, covered by

stone tiles tikli. The windows were laid high in the sub-ceiling structure and

provided fine lighting in the interior of the church.

The story

of the permit obtained hard from the Turkish Authorities to build the church

turned into a local legend tells for a famous Kovachevitsa merchant that managed

to receive recognition even in the Sultan’s Court in Tzarigrad as being a skillful

barber. His fellowvillagers asked him for assistance since it had been impossible

for them to receive a construction permit from the Sultan Administration (the

High Gate). The latter was done by Sultan himself who issued and signed a firman

for the construction of the Kovachevitsa church as a sign of benevolence and

recognition of the Kovachevitsa barber’s talent. The only condition was that

it should not be raised tall in order not to been seen from a large distance.

Therefore, the builders dug the church into the ground and yet preserved its

large size in the interior. The entire community worked to build this God’s

temple and maybe that is the reason why the craftsmen forgot to engrave their

names in a commemorative tablet on the wall or probably the sponsors were that

numerous and it was difficult to fit onto one wall. The church was completed

and sanctified in 1848. The St. Nikola basilica with a nave a two aisles, one

of the five largest basilicas in Bulgaria, was built following the traditional

Kovachevitsa technique and materials, solid stone walls and top, covered by

stone tiles tikli. The windows were laid high in the sub-ceiling structure and

provided fine lighting in the interior of the church.